Effective planning involves a reduction of improvisation in projects

One of the most common characteristics of Colombians is our tendency toward short-term thinking. We often act based on immediate needs without considering long-term consequences. This is human nature, but culture can either amplify or mitigate it. We can observe this behavior in our personal finances, health decisions, diet, conversations, news content, and more. It’s what behavioral economists call present bias — favoring short-term benefits over long-term gains.

This mindset is especially evident in politics and economics. However, I’d like to focus on the construction sector. In the way we plan our cities, buildings, and renovations, we often cut corners on planning and spend more time “putting out fires.” While we chase short-term wins, more developed countries invest in infrastructure planning that considers the next 80 to 100 years of growth and demand.

In construction, several causes contribute to this reactive approach:

- Humans haven’t always had the cognitive ability to think abstractly about the future.

- Political cycles push elected officials to prioritize short-term results that align with re-election, rather than long-term societal wellbeing.

- We underinvest in engineering. We’re often “stingy” with consulting services during feasibility and preconstruction, leading to poorly conceived or designed projects (often investing less than 5% of the budget in value engineering, planning, or risk analysis).

- Projects typically reach the detailed design stage only once construction, environmental, and financial permits are secured — which logically makes sense, but leaves too little time for comprehensive planning before execution.

- Traditional planning processes focus more on activity sequencing than on the continuity of workflow across multiple contractors.

From our experience at Entrez and supported by literature, these factors lead to excessive improvisation in projects. As a result, we consistently fall short on time, cost, quality, and safety goals. Improvisation also takes a human toll: stress, alienation, and a lack of innovation. Our industry remains stuck in old routines, blocking creativity, lateral thinking, and disruptive ideas. Caught in daily firefighting, we fail to explore better ways of doing things, creating value, and improving business processes. “We build like we did 30 years ago,” people say in the hallways. Worse still, we excel at retaining non-value-adding processes that drain productivity — a loss well-documented by McKinsey, Camacol, CCI, and others.

That’s why I invite all of us — especially those in leadership and decision-making roles — to pause and reflect on our shared project objectives. We must make timely decisions that prevent improvisation during execution. Remember: bad news is valuable when it arrives early. The earlier we know something is wrong, the more time we have to mitigate its impact and take corrective action.

- Use of parametric, multidimensional models (BIM) with a clear purpose. Virtually constructing a project encourages — or forces — the project team to make decisions in advance, instead of leaving them for the construction site when options are limited. This approach strengthens planning and reduces improvisation.

- Implementation of the Last Planner System (LPS). Through collaborative planning (pull planning), LPS encourages the team to think mid- and long-term in order to ensure short-term workflow. LPS enables early visibility of problems — often before they fully materialize — allowing the team to respond proactively.

Specifically, the third of the four LPS planning phases directly addresses the problem outlined earlier: the Make-Ready or Lookahead phase, where we plan to remove constraints on tasks scheduled for the next 6 to 10 weeks. Once tasks are constraint-free, they become executable — meaning they can be started and completed. Only then do they make sense to schedule in the short-term plan. LPS has proven to improve workflow continuity and planning reliability by minimizing the gap between what is planned and what is actually completed.

LPS includes performance metrics. The reliability of workflow is typically measured by the Percent Plan Complete (PPC) — the percentage of tasks completed at the end of a fixed period relative to those planned at the start. For early planning performance, Tasks Make Ready (TMR) is used. TMR measures how well teams identify and remove constraints to prepare tasks for execution. TMR(i, j) refers to the percentage of tasks made ready in the plan i weeks before execution week j.

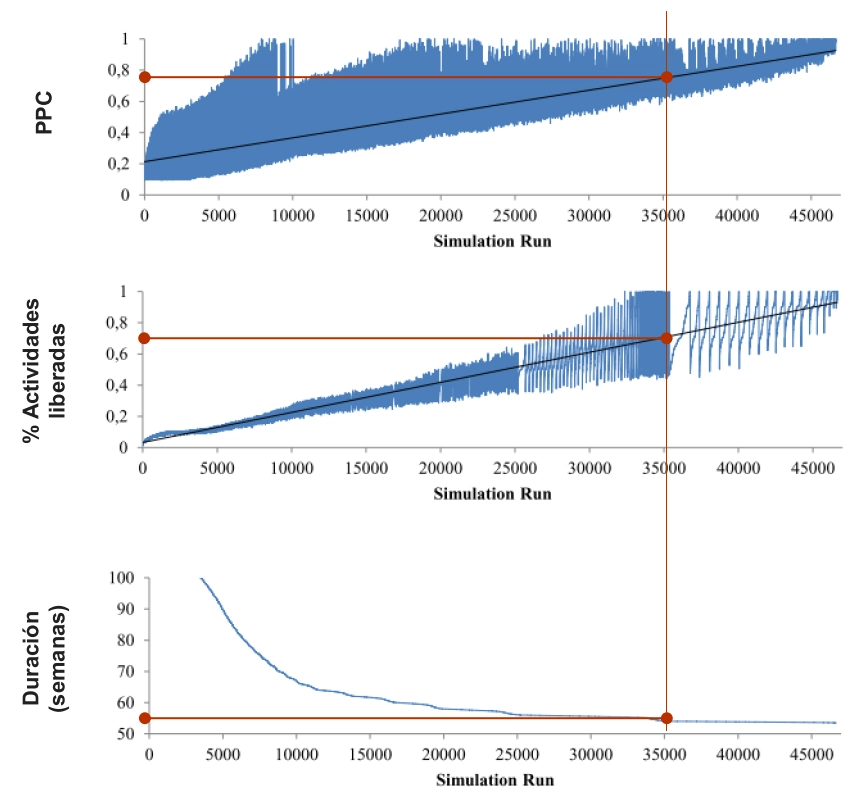

In the referenced study, Hamzeh et al. (2016) present simulation results exploring the relationship between % Tasks Made Ready, PPC, and overall project duration. The results confirm the critical role of the Make-Ready process: removing constraints directly impacts project duration.

Illustration 1. Graphs showing the relationship between PPC, Tasks Make Ready (TMR), and project duration across simulations (Hamzeh et al., 2016).

As the top graph shows, project duration clearly decreases as the % of Tasks Made Ready increases. However, beyond a certain point, the duration reduction flattens and becomes asymptotic. The study shows that while a high % of Tasks Made Ready leads to shorter projects, the same cannot always be said for PPC (which relates more to productivity). Thus, TMR is a better indicator of project duration than PPC.

In conclusion, companies in the construction sector must adopt planning tools that encourage early collaboration. Let’s embrace the power of technology and use short-term focus for execution — but plan for the medium and long term. Focusing on removing task constraints boosts the likelihood of meeting or even shortening project durations. Early warnings are good news. By doing so, we can reduce the improvisation that holds back our construction projects — and move toward better outcomes, less stress, more innovation, and higher productivity. We must rise to the level of our potential.